Minor third

Most bird song isn’t what we’d recognise as regular musical intervals, but there are exceptions. A peculiarity of those exceptions is how often the ‘minor third’ seems to crop up.

Though known by many from European cuckoos, more surprising is how – it seems to me – the minor third seems to be the interval of choice across a range of species. Is this fair? This web page is to put my observation in writing and to invite comment and debate.

Musical intervals

Firstly, a quick note for non-musicians. A musical interval is the gap between notes. Sing the first two notes of ‘Amazing Grace’ and you’re just sung a fourth. ‘Baa baa black sheep’ kicks off with a fifth. Beach Boys fans hear a sixth as Brian Wilson sings ‘Surfer Girl’. If that doesn’t work for you, ‘My Bonny lies over the ocean’ also starts with a sixth.

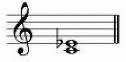

So what about the minor third? It’s the interval of the second 'da da da DA' of Beethoven’s Fifth (the first is a major third). It’s the slightly poignant yet penetrating ‘Ne na ne na’ of an old-fashioned ambulance – before today’s wailing sirens were introduced.

The children's traditional playground cry "naa naa na naa naaa" is based around a minor third (taunts that would discouraged nowadays). Primary school music teacher Jacqui Burke says that: "Usually the first word a child learns eg., ‘ mummy, mama’ is pitched to the soh/mi interval."

An octave is the interval between one musical pitch and another with half or double its frequency (depending on whether you go down or up.) These notes starts from the assumption that to divide an octave into eight notes (12 equal semitones) is a musical structure made by western man. (The Arabic classical scale has 17, 19, or even 24 notes – perhaps why music from a minaret sounds uncomfortable to western ears).

But are there any grounds in physics or nature to argue that our notes are more natural than that – or copied from nature in some way?

The cuckoo

The minor third is the cu-coo of a cuckoo in spring. This is fairly well-known. It crops up in classical music (see right): Google it and you’ll find a list of references including a blog at Springwatch.

But the sound doesn’t stay like that all season.

Cuckoos are known to change their song during the spring and early summer – see the rhyme on the right. The interval moves, roughly, from a minor third to a major third to a fourth. This is not clear-cut: sometimes you can hear the later, bigger intervals early in the season; in May, to hear a mixture is not unusual. Sometimes the intervals aren’t completely clean, to our ears.

But these are details. The best-known and much loved interval, at the start of spring, is a minor third.

Ortolan bunting

|

Many years ago, I recall Honeyguide leader Robin Hamilton enthusing over the ortolan bunting's ‘Beethoven’s Fifth’ song. The rhythm recalls Beethoven's famous da - da - da - daah. It’s hardly a top songster, but listen carefully and the interval (as I hear it) is also a minor third. Sometimes it goes up: sometimes it goes down. But my experience in the field is that it’s always a minor third – though that’s not clear on the recording on Jean Roché’s ‘Bird Songs and Calls of Britain and Europe’ CD set. |

Common crane

Two birds, one interval: an intriguing link. But there are more. The so-called ‘unison’ bugling of common cranes is, in fact, close harmony. According to Birds of the Western Palearctic, it’s another minor third – though again that not clear on the recording on Jean Roché’s CD set.

This call is often made on or near the nest, and when courting, but also frequently out of the breeding season when crane pairs are feeding or walking around. It seems to be a contact call, acting as reassurance when the other bird joins in. More on European cranes in Norfolk here.

South African birds

In autumn 2009, I was in South Africa’s Garden Route. We heard red-chested cuckoos (Piet my Vrou bird) , a widespread bird species south of the Sahara, on several occasions. The song goes down the scale from (roughly) C sharp, C natural, B flat, like ‘Three Blind Mice’ played in a minor key. Hear it here or here.

From its top note to its bottom note: a minor third, again, albeit with one extra note in the middle.

Then, at the rhinoceros hide in Addo Elephant National Park, a bird, probably a bokmakierie (a kind of shrike) was singing the introduction to Beethoven's Fifth symphony. Sadly, I couldn’t see the bird to confirm its ID.

What’s the link?

Why should the minor third crop up like this? So far as I know, this connection hasn’t been described before and there are no clear theories or conclusions.

The purpose of bird song is to mark territory and to attract a mate. Given birds’ relatively limited vocal range, perhaps larger musical intervals come less easily, and a simple tone or semi-tone is less distinctive for communication.

So is the minor third be a ‘natural’ interval that comes easily to birds? Surely that’s too anthropomorphic? Perhaps it’s just coincidence.

I welcome comments, information and opinions! To email, click here.

Back to nature notes Chris Durdin, February 2010, with later updates